Canada and the great power rivalry: What options are left for the EU?

Canada is often seen as one of Europe’s last remaining like-minded partners on the global stage. In response to U.S. tariffs under President Trump and Washington’s growing geopolitical assertiveness, Ottawa has sought closer ties with the EU, particularly by broadening its economic diversification. Paradoxically, however, Canada’s resource sector remains dominated by China. Europe will remain geopolitically constrained unless it finally takes strategic action.

By Prof. Dr. Michael Hüther und Dr. Simon Gerards Iglesias

The recently concluded trade agreement between the United States and the EU marks a clear departure by the former guarantors of the post-1945 global trading order from a rules-based globalization founded on most-favored-nation treatment, reciprocity, transparency, and liberalization. What is emerging instead – replacing the free and multilateral exchange of goods and capital that benefits all parties – is inward-looking trade, justified in security terms and increasingly based on bilateral relationships.

In addition to a new tariff regime, the agreement commits the EU to increasing its annual energy imports from the United States to 250 billion USD by 2027 and to undertaking direct investments worth 550 billion euros by 2029. Although these tasks – especially investment decisions – ultimately rest with European companies, doubts persist about the EU’s actual need for imported energy, particularly oil and gas. In 2024, the total value of such imports amounted to 384 billion USD, with U.S. deliveries accounting for about 66 billion – just one quarter of the stated target.

“Closer cooperation with Canada could help Europe.”

The United States remains indispensable to the EU – above all in military and security matters, but also economically. Yet the EU must make far greater efforts than before to reduce this dependency. Closer cooperation with Canada could help in this regard, but Canada itself is a prime target of Donald Trump’s expansionism and is deeply enmeshed in the U.S. economy.

Canada, a natural resource powerhouse

Canada shares an 8,900 km (5,500 mile) land border with the United States and is bound by a trade agreement that has resulted in deep economic integration among the North American economies, particularly in the automotive sector. The USMCA agreement, which at Trump’s initiative replaced NAFTA in 2020, shields 95 percent of traded goods from the new tariffs he imposed on his northern neighbor. (Hughes, 2025).

Canada is a resource-rich country. One-fifth of its exports consists of critical minerals and metals, including aluminum, copper, nickel, platinum, and zinc. Over half of these exports are destined for the United States, followed by China, the UK, Japan, and the EU. Owing in part to the world’s largest yet untapped reserves of rare earth elements, Canada has become a target in the intensifying rivalry among major powers – a competition that is increasingly defined by access to and control over critical raw materials. Since 2016, a negotiated trade agreement has been in place between the EU and Canada, although it has still not been ratified by all EU member states. In the context of the Critical Raw Materials Act, they have also established a strategic partnership aimed at encouraging companies to source more raw materials from Europe and North America (Carry, 2024).

Europe’s dependence on raw materials

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has brought Europe’s reliance on imported raw materials into political focus. Terms such as strategic autonomy, friendshoring, and resilience have since become staples of foreign economic policy discourse. Particularly, the dependence on rare earth elements from China is now widely acknowledged as a political commonplace. Yet, German and European companies have so far shown little evidence of diversification, especially when it comes to critical raw materials (Becker, 2025).

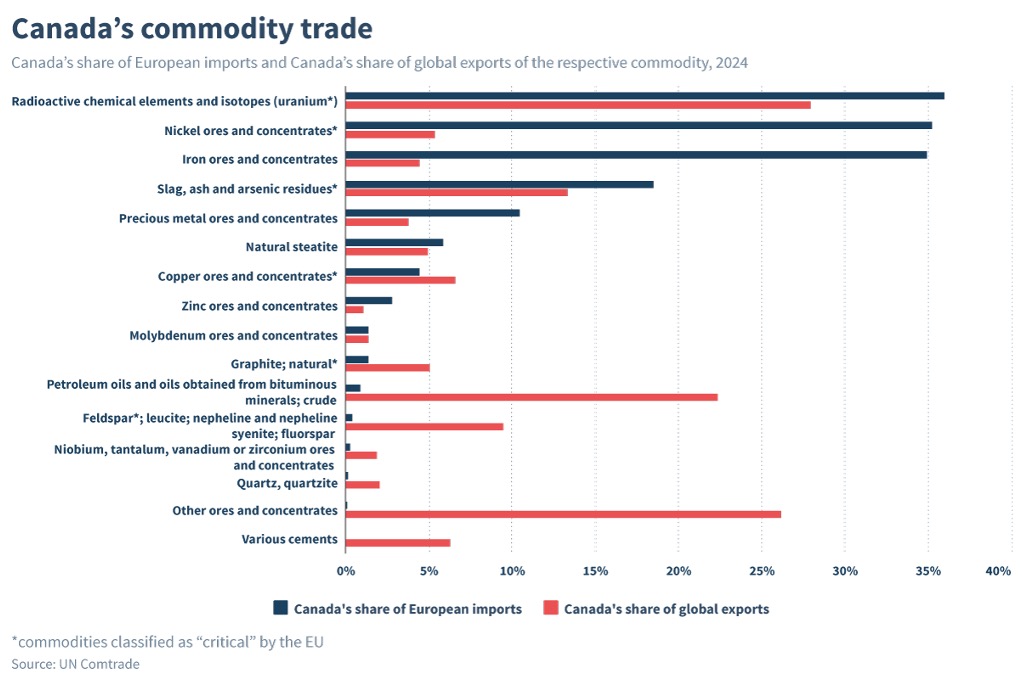

The picture is ambivalent. Figure 1 shows Canada’s share of total EU imports and of global exports for selected raw materials in 2024, focusing on its most important export commodities. This allows for a comparison of where Canada is over- or underrepresented in EU raw material imports. For uran elements, nickel ores, iron ores, arsenic, precious metals, and zinc, Canada’s share of EU imports is significantly higher than its share of the global market; for molybdenum, it is nearly equal. In the case of crude oil, copper, graphite, feldspar, and other rate earth elements, however, Canada is strongly underrepresented as a supplier to the EU. Many of these latter materials are classified as “critical” by the European Commission and that are of central importance for the green transition (batteries, wind power, steel products) as well as for strategic autonomy (electrical industry, semiconductors, aerospace).

These differences are largely explained by the fact that for most raw materials in Canada there is a monopsony – one principal buyer dominating the trade. In most cases, this buyer is the United States (e.g., nickel, arsenic, feldspar, graphite). However, in the category of “other ores and concentrates”, which includes rare earth elements, 99 percent of Canada’s exports go to China. China holds majority stakes in the largest Canadian mining companies and controls domestic processing, giving it complete command over the supply chain and raw material pricing (Carry, 2024). Over 90 percent of processing technologies for rare earths (magnets, specialty ceramics, and alloys) worldwide are controlled by China. For lithium and cobalt, the figure is 60 to 70 percent (Public Policy Forum, 2025), extending this technological dominance to foreign markets as well. Canada’s case shows how China entrenches its position in key technology markets abroad, making diversification a far steeper challenge for Europe.

Direct investment as geopolitical weapon

Canada possesses large reserves of critical raw materials that remain largely untapped but are economically viable. The country depends on foreign direct investment to exploit these resources, with 40 to 45 percent of mining investments coming from abroad (Leach et al., 2025). Since the COVID-19 pandemic, China has considerably increased its investments in Canadian mining and has been by far the largest investor since 2021. Nearly 50 percent of all new FDI activity in Canadian mining in 2024 originated from China, followed by the U.S. with 30 percent, while Europe accounted for only 13 percent (Statistics Canada, 2025). Between 2014 and 2019, Europe was the leading foreign investor in Canadian mining – a situation that has changed dramatically.

The EU and Canada are natural partners

To gain greater autonomy in the rivalry between the major powers, the United States and China, and to offer a genuine third alternative, the EU and Canada must deepen their partnership. Canada has recently tightened rules on foreign direct investment, particularly targeting Chinese companies (Borgers et al., 2025), yet still regards the United States as its most important partner. However, Washington’s growing expansionist ambitions run counter to Canada’s approach, which places strong emphasis on human rights (including Indigenous rights) and green sustainability (Sustainable Critical Minerals Alliance). The EU can build on these shared priorities, but it must also be prepared to temper its maximalist demands in international agreements.

The ongoing controversy over CETA has repeatedly centered on arbitration tribunals – mechanisms that are nonetheless crucial to transnational investments, especially in the high-risk mining sector. The fact that CETA still awaits ratification in several EU member states should serve as a warning. If the EU is to rank among the world’s technological and economic leaders, it must prioritize geostrategic considerations over its aspiration to be the global standard-setter.

About the authors:

Prof. Dr. Michael Hüther is Director of the German Economic Institute (IW) in Cologne and Deputy Chairman of Atlantik-Brücke. Dr. Simon Gerards Iglesias is personal advisor to the Director at the IW. This article first appeared as an IW short report.

References

Becker, Markus, 2025, Rohstoffabhängigkeit von China bedroht EU-Wirtschaft, https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/seltene-erden-rohstoff-abhaengigkeit-von-china-bedroht-eu-wirtschaft-a-a0f210e6-983f-4dcc-865d-3ae8bfd69d7f?giftToken=0b2c997a-2065-4760-930d-1970fb89318c [13.08.2025]

Borgers, Oliver / Gudofsky, Jason / Kwinter, Gideon / Keogh, Erin, 2025, Foreign direct investment reviews 2025: Canada, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/foreign-direct-investment-reviews-2025-canada [13.08.2025]

Carry, Inga, 2024, Rohstoffpartner Kanada: ein (nahe-zu) perfekter Match. Die europäisch-kanadische Rohstoffkooperation in Zeiten des Friendshoring, SWP-Aktuell, Nr. 27

Government of Canada, 2024, Mineral Trade, https://natural-resources.canada.ca/maps-tools-publications/publications/mineral-trade#tbl3, [13.08.2025]

Hughes, Abby, 2025, The U.S. bumped its tariff on Canadian goods to 35%. How big of an impact will it have?, https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/what-in-canada-is-subject-to-35-per-cent-tariff-1.7600029 [13.08.2025]

Leach, Cynthia et al., 2025, Critical Capital: How Canada can tap foreign investment for its mineral riches, https://www.rbc.com/en/thought-leadership/uncategorized/thought-leadership/critical-capital-how-canada-can-tap-foreign-investment-for-its-mineral-riches/ [13.08.2025]

Public Policy Forum, 2025, How Canada could quickly develop critical materials, LINK [08.08.2025]

Statistics Canada, 2025, International Investment Position, https://ppforum.ca/policy-speaking/how-canada-could-quickly-develop-critical-minerals/ [13.08.2025]

Statistics Canada, 2025, International Investment Position, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610000801 [13.08.2025]