“As long as we remain fragmented, we will always rely on Washington”

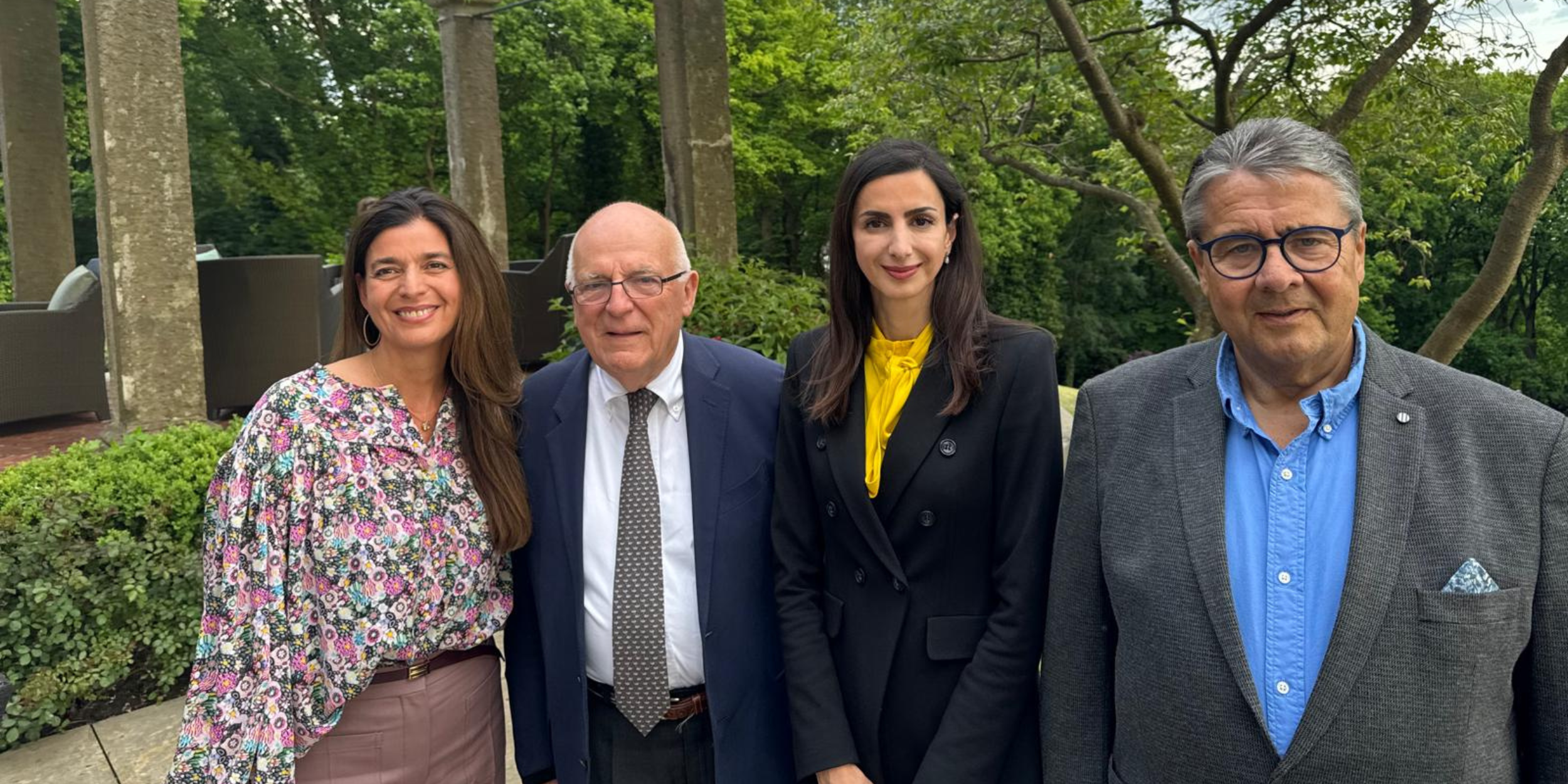

Within a shifting global landscape, foreign intelligence services are coming into sharper focus – not only as instruments of national security, but also as influential actors in international politics. Under the title „The Power of Intelligence: How Information Shapes Global Politics“ our Chairman and former vice chancellor Sigmar Gabriel and Sir Richard Dearlove, former Chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service MI6, discussed this development with our Regional Chapter Hamburg. The event was hosted by Nagila Warburg and Max Warburg and moderated by Anahita Thoms.

In the following interview, Sigmar Gabriel discusses the development of intelligence services since the end of the Cold War, Europe’s dependence on US intelligence information, and greater resilience against cyber attacks.

How has the approach and influence of secret intelligence services changed since the end of the cold war?

After the Cold War, the role of intelligence services changed fundamentally. During the East-West conflict, it was mainly about military intelligence and strategic deterrence. Today, the threats are much more diverse — ranging from international terrorism to cyberattacks, hybrid warfare, and state-sponsored disinformation.

This has expanded the influence and scope of intelligence agencies significantly. But with that comes a real challenge for democracies: how to ensure proper oversight and accountability. Intelligence work must remain bound to the rule of law and democratic principles.

We also see that no single country can effectively respond to these complex threats alone. International cooperation—especially among democratic nations—is more important than ever. Intelligence must not become a tool of unchecked power, but a part of a responsible security strategy in service of our democratic values.

Following the dispute between Trump and Selensky at the White House, the U.S. briefly withdrew Ukraine’s access to intelligence information on Russian troop movements and the early detection of missile attacks in March. Ukraine’s other allies were unable to provide this information. How can Ukraine and its European allies reduce its dependence on US intelligence services?

The mentioned incident shows how fragile reliance on a single partner can be — even when that partner is the United States. We should not misunderstand this: the transatlantic alliance remains essential, and the U.S. contribution to Ukraine’s defense has been decisive. But this moment also reminds us in Europe of a painful truth: we are still far too dependent on American intelligence and defense capabilities.

To reduce this dependence, Europe must strengthen its own strategic autonomy — not in opposition to the United States, but to be a more capable and reliable partner. That means investing in our own satellite systems, surveillance capacities, early-warning systems, and better coordination among European intelligence services.

Ukraine should also be more closely integrated into European defense structures. But for that to work, Europe itself needs to become more unified and capable. As long as we remain fragmented, we will always rely on Washington in moments of crisis. The goal should not be independence from the U.S., but resilience and partnership at eye level.

Cyberattacks are becoming increasingly frequent. In March, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution warned non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and scientific institutions of potential attacks. Politicians are also being targeted more often, including through phishing emails designed to gain access to their passwords and confidential information. How can democracies effectively defend themselves against this threat?

Cyberattacks are not just a threat to democratic institutions, they’re an economic and geopolitical risk. When NGOs, research institutions or politicians are attacked, it’s often part of a broader strategy by hostile states to weaken democratic societies from within.

But let’s be clear: behind many of these attacks are state or state-sponsored actors pursuing strategic interests, economic espionage, political disruption, or technological sabotage. Democracies must respond in kind—not naively, but with clear-eyed realism. We need to build serious cyber defense capabilities at the European level, including for critical infrastructure and key industries. That means investing in our own digital technologies, reducing dependence on non-European providers, and ensuring that companies and research institutions are part of the security network.

At the same time, we must increase deterrence. That includes naming and shaming aggressors, applying sanctions where necessary, and defending our digital sovereignty. In the 21st century, the resilience of democracies will depend not just on tanks and treaties, but on cybersecurity and technological self-reliance.